- Processes

- Polymer Processing

- Blow Molding

- Injection Molding

- Metal Injection Molding

- Thermoforming

- Metal Casting

- Centrifugal Casting

- Die Casting

- Investment Casting

- Permanent Mold

- Sand Casting

- Shell Mold Casting

- Machining

- Milling

- Turning

- Hole-making

- Drill Size Chart

- Tap Size Chart

- Sheet Metal Fabrication

- Forming

- Cutting with shear

- Cutting without shear

- Gauge Size Chart

- Additive Fabrication

- SLA

- FDM

- SLS

- DMLS

- 3D Printing

- Inkjet Printing

- Jetted Photopolymer

- LOM

- Materials

- Metals

- Plastics

- Case Studies

- Cost Analysis

- Part Redesign

- Product Development

- Resources

- Curriculum Resources

- Glossary

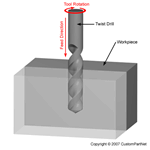

Hole-making is a class of machining

operations that are specifically used to cut a hole into

a workpiece.

Machining, a material removal process,

creates features on a part by cutting away the unwanted

material and requires a machine, workpiece,

fixture, and

cutting tool. Hole-making can be performed on a variety

of machines, including general machining equipment such

as CNC milling machines or CNC turning machines.

Specialized equipment also exists for hole-making, such

as drill presses or tapping machines. The workpiece is a

piece of pre-shaped material that is secured to the

fixture, which itself is attached to a platform inside

the machine. The cutting tool is a cylindrical tool with

sharp teeth that is secured inside a piece called a

collet, which is then attached to the spindle, which

rotates the tool at high speeds. By feeding the rotating

tool into the workpiece, material is cut away in the

form of small chips to create the desired feature.

Hole-making operations are

typically performed amongst many other operations in the

machining of a part. However, hole-making may be

performed as a secondary machining process for an

existing part, such as a casting or forging. This can be

done to add features that were too costly to form during

the primary process or to improve the tolerance or

surface finish of existing holes.

Machined holes

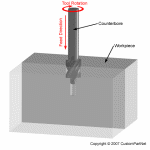

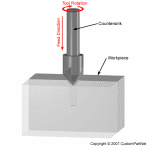

In machining, a hole is a cylindrical feature that is cut from the workpiece by a rotating cutting tool that enters the workpiece axially. The hole will have the same diameter of the cutting tool and match the geometry (which may include a pointed end). Non-cylindrical features, or pockets, can also be machined, but they require end milling operations not hole-making operations. While all machined holes have the same basic form they can still differ in many ways to best suit a given application. A machined hole can be characterized by several different parameters or features which will determine the hole-making operation and tool that is required.

- Diameter - Holes can be machined in a wide variety of diameters, determined by the selected tool. The cutting tools used for hole-making are available in standard sizes that can be as small as 0.0019 inches and as large as 3 inches. Several standards exist including fractional sizes, letter sizes, number sizes, and metric sizes. A custom tool can be created to machine a non-standard diameter, but it is more cost effective to use the closest standard sized tool.

- Tolerance - In any machining operation, the precision of a cut can be affected by several factors, including the sharpness of the tool, any vibration of the tool, or the build up of chips of material. The specified tolerance of a hole will determine the method of hole-making used, as some methods are suited for tight-tolerance holes.

- Depth - A machined hole may extend to a point within the workpiece, known as a blind hole, or it may extend completely through the workpiece, known as a through hole. A blind hole may have a flat bottom, but typically ends in a point due to the pointed end of the tool. When specifying the depth of a hole, one may reference the depth to the point or the depth to the end of the full diameter portion of the hole. The total depth of the hole is limited by the length of the cutting tool.

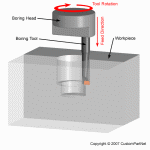

- Recessed top - A common feature of machined holes is to recess the top of the hole into the workpiece. This is typically done to accommodate the head of a fastener and allow it to sit flush with the workpiece surface. Two types of recessed holes are a counterbore, which has a cylindrical recess, and a countersink, which has a cone-shaped recess.

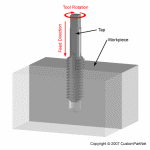

- Threads - Threaded holes are machined to accommodate a threaded fastener and are typically specified by their outer diameter and pitch. The pitch is a measure of the spacing between threads and may be expressed in the English standard, as the number of threads per inch (TPI), or in the metric standard, as the distance in millimeters (mm) between threads.

Return to top

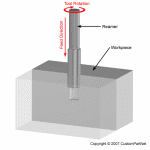

Hole-making operations

Several hole-making operations exist, each using a different type of cutting tool and forming a different type of hole.

Return to top